Hunting collisions with ntHash

By Víctor Rodríguez Bouza

This blog post summarises some checks and comprobations done while developing Sparrowhawk after we discovered an unsettling surprise. The first two sections explain quickly what a genomic assembler is and the issue we found during the development (bad performance when assembling at large k values), and why it prompted us to study hash collisions as a potential cause for this. If you are here only for the hashes and the collisions, jump directly to the third section (ntHash and collisions).

A quick introduction

Sparrowhawk is a new genomic assembler we are currently developing in the group. A genomic assembler, or just “assembler”, tries to put back together a genome from the raw data that genomic sequencing devices provide. This data consist on many fragments called reads, that are obtained from the original genome by multiplying it and randomly splitting the sequence. This is done to tackle the sequencing errors these devices might have: given that the genome is multiplied, the reads cover various times (we call coverage this amount) the complete genome and thus we can differentiate from one read that has a sequence with a sequencing error from the rest that hopefully (given that errors are not very frequent!) will represent the actual sequence.

Because of the unequal splitting, assemblers commonly rely on subsequences of fixed size that are afterwards linked together to attempt to recompose the genome. We call these strings also k-mers: subsequences of length k. And it is quite common to extract those k-mers from your reads and count them, to avoid e.g. the sequencing errors we mentioned. These k-mers can be later linked together in a de Bruijn graph, a structure that basically links the k-mers that share k-1 nucleotides.

It is quite convenient to work with different k values, because that allows you to resolve repeats in the genome. For example, if you had a read from one sequencing experiment that was

GTATTATTATTAC

and you worked with 3-mers in your assembler, you would only extract from that the 3-mers

GTA, TAT, ATT, TTA, TAC

and you would not be able to see the repeat of the ATT motif. However, with a larger k value, say 6, you’d find

GTATTA, TATTAT, ATTATT, TTATTA, TATTAC

from which you can completely recover the exact original sequence. To work with different k-values, it is common to resort to using hashing functions, that essentially map something to a particular value (usually a number) that almost always have a fixed size. With them you can work with k-mers of very large sizes and do your calculations always, in your software, with the same sized variable, say an integer of 32 bits. The assembler we are working in, Sparrowhawk, uses hashing for working with fixed size (64 bits) variables in all cases, using a fast rolling hash function called ntHash.

The ultraviolet catastrophe

One thing I wanted to do as soon as we had something that we could call (despite the many caveats) an assembler, was a benchmark. Or, with other words, a systematic evaluation of the performance of our software, as well as its comparison with other existing programs that aim for the same. I did it using six different bacterial species, taking one reference assembly from each of them, and using both ART and Mason to generate 30 simulations of each of the six assemblies. I also collected 30 real sequencing raw data (reads) from ENA from each of the six species. Then, I plotted some figures of merit against different k values and compared the status at that time of Sparrowhawk with other four assemblers: Velvet, Minia, Skesa, and Spades.

The early results gave a lot of data to analyse! And although some improvements for the comparison surged quickly in my mind, more or less we got some key takeaway messages:

- Overall, and roughly for both simulations and real reads, Sparrowhawk does a similar job as Minia and/or Velvet, usually improving over the last one. Spades and Skesa offer better results in general.

- Given that our error correction measures are almost inexistent, it is quite good and encouraging that we are getting these results!

- And something happens at large k values…

One of the early benchmark results

For some reason, usually after something like k=50-60, the values of the observables we were using for Sparrowhawk declined: for all species, and both simulations and real reads. I had some ideas of what could be behind this ultraviolet catastrophe, and one was hash collisions.

ntHash and collisions

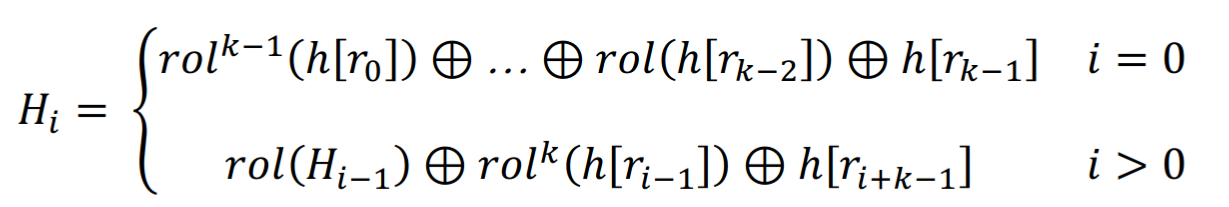

ntHash in its original version works by reading, nucleotide per nucleotide, a k-mer. For each of the nucleotides, it circularly rotates the bits to the left (the “rol” function below) various times a particular number or word (four in total, one per base) of 64 bits. And then it computes the hash of the k-mer by XORing (the + symbol with a circle) these rotated words and obtaining a hash of 64 bits. It is fast and allows for rolling it, i.e. calculating the hash of an adjacent k-mer by removing the contribution from the first nucleotide (the base to erase) and adding the contribution of the new one.

ntHash version 1 definition

This poses a problem, as discussed in this GitHub issue. When you hash k-mers with k>64, given that rotating a cycle either to left or right the same number of times as its length gives you the same result, you could end up with, inside the hash calculation,

hash = rol(h(s[0]), 64) ^ … ^ rol(h(s[64]), 0) = rol(h(s[0]), 0) ^ … ^ rol(h(s[64]), 0)

with ^ representing XOR, and rol(a, b) being the rotate to the left b times the a word. But, as XOR is commutative and a ^ a = 0, then those two terms (with bold font in the example) can be eliminated if e.g. they correspond to the same nucleotide. Consequently, the probability that ntHash gives the same hash for different k-mers (a “collision”) when k>65 increases, as this symmetry can erase part of the variability of these hashes.

They fixed it in ntHash version 2, by replacing the rol function with srol. This essentially increases the period from 64 to a much larger number by simply rotating, instead of the entire 64 bit word, parts of it independently. For instance, the basic ntHash2 implementation splits the words into two: 33 bits at the left, and the remaining 31 at the right. Thus, the period in which the same situation happens will be when the periods of both “subwords” align, i.e. their least common multiple, which is 1023: two orders of magnitude larger than 64! This reduces the probability of these kind of collisions.

The checks

I tried to first see if there were collisions actually in the benchmarking assemblies of Sparrowhawk. And unfortunately… they were! Curiously, only after k=64, i.e. from 65 onwards. For both simulations and reads, although simulation’s were very few compared with reads: this could be logical, as in many of the reads the coverage they have is larger than what we had in the simulations. In any case, the fact that the collisions only started after k=64 was suspicious.

I was mostly convinced soon that the collisions would surely not explain the bad performance at high k, as they happened in very few of the cases: however it was worth looking a bit more at them, first because they might have been an indicator of an underlying bug somewhere, and secondly because they affect the results of the assembler itself.

The first thing I did thus was review our ntHash2 implementation, looking for potential bugs. After checking that there were not any that I could find, I concluded the collisions were real, not fake, a thing that I confirmed later by creating a small Rust script to calculate the hashes separately from the Sparrowhawk code, using k-mers that while running Sparrowhawk had collisions.

Given the design of ntHash (both v1 and v2) we could think of two origins for any collision we might have. The first is the set of collisions that arise because of the period issue that motivated the second version of ntHash. The other group are those collisions that happen without that particular “help”, and that are present in ntHash itself. If the collisions come from the latter set, and we decided to remove them, we would need to change the ntHash function itself, or use an extra hashing function, or something more complicated. Consequently, I decided to check first whether the collisions we were seeing perhaps corresponded to the first group.

Given that the basic ntHash version 2 implementation has only two splits to tackle the period issue, it is logical to think that perhaps that 1023 period was not enough. To check it, I went back to the ntHash2 paper, where they describe in the supplementary material how this period issue appears and how to fix it. They also give the optimised splits you can make of a 64 bit integer already, that can be done up to seven splits. Thus, I decided to test with more splits to see if we could reduce the collisions that way (and consequently, most probably, the collisions would be of the first group).

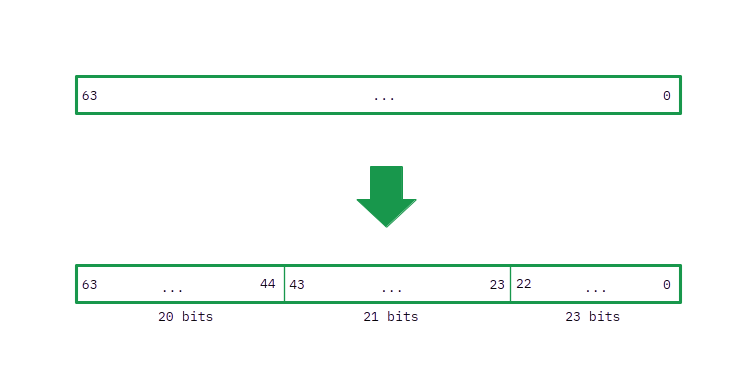

The implementation is slightly tricky (especially if you are not used to work with bitwise operations!) and requires to take care in knowing exactly what bits from the integers you want to cycle. According to the supplementary material of the article, the optimised split of a 64 bit number that increases the period to 9660 has three parts of 20, 21, and 23 bits. You can see a representation here (note that the right are the bits that are least important, and that the indexes grow to the left from zero, i.e. the rightmost bit is the first one with index zero and the leftmost one is the last bit in the 63rd location):

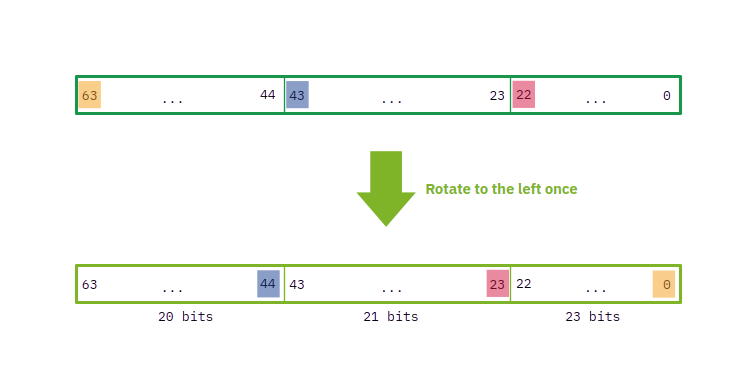

There are two main operations to be implemented: building the first hash, and rolling it afterwards. The rest is essentially the same. For building the hash we will need to rotate to the left these three parts of the four “special words” (or numbers: one of each assigned to each nucleotide) a number of times depending on the position of the particular nucleotide inside the k-mer. A simple way of doing that only once is, instead of separating the bits of each part from the others and rotate them, to just rotate the entire number to the left once and then change the position of some bits. So, if we rotate once the entire number to the left, the previous bits will be located in these new positions:

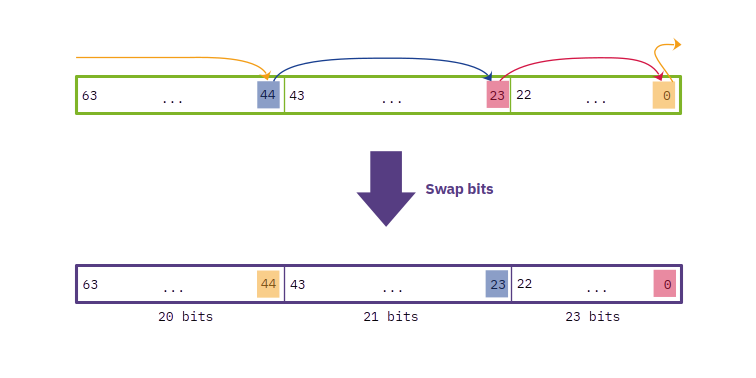

This is not what we want, but if we look closely, to get the word with the separated parts individually rotated to the left once, we just need to exchange some bits of position! In particular, for this case, the bit that previously was in the last position (63) and now is in the first one (0) needs to move to the position 44, because that is the first position of the first part of 20 bits. Analogously, the bit that now is in the 44th position needs to move to the right to the 23rd position, which is the first bit of the second part of 21 bits. And finally, the bit in the 23rd position needs to be the first bit of the whole number and consequently of the last group of 23 bits. If we do that, we obtain:

That is what we wanted. To do this in Rust we can take advantage of some bitwise operations that make this easy: using right-shifts (»), and bit-wise ANDs (&), ORs (|), and XORs (^), we can implement this quickly as:

pub fn swapbits_0_23_44(v: u64) -> u64 {

let x = ((v >> 44) ^ (v >> 23)) & 1; // The 23rd bit XOR the 44th

let y = (v ^ (v >> 44)) & 1; // The 44th bit XOR the 0th

let z = (v ^ (v >> 23)) & 1; // The 23rd bit XOR the 0th

v ^ (z | (x << 23) | (y << 44))

}

This helps implement the srol function of ntHash2. To complete implement ntHash2 with three splits, we also need to create look-up tables with all the rotations of the three parts of the four words/numbers and store them, to increase the speed of it. This can be done easily with an easy Python script and then copypaste the tables into your Rust code.

Once I did this, and given that running these checks takes some time, I also run the equivalent for six splits of size 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, and 19 bits, that increases the period to a much larger value: 855855. Afterwards, I ran the same checks as before to count collisions.

The results with three splits were… different! We definitely still got collisions, and also with k-values smaller than 64! However, the global amount of collisions was smaller than with the default two splits. If with default ntHash we obtained, especially for the real data (no simulations) and mainly from Streptomyces avermitilis assemblies, the order of tens (even hundreds!) of thousands of collisions, we now saw orders of tens or hundreds of collisions mostly.

Where there was a significant decrease was with six splits: we only saw a total of four collisions in the same reads that previously generated up to hundreds of thousands of collisions! This was certainly a difference with what we had earlier.

Summary

Given the significant decrease in the collisions showed by adding splits, it seems that most if not all of the collisions we were having were related with the period issue. Probably, for the coverage some ENA downloaded reads had there was enough variability to overcome the 1023 period. However we can overcome this by increasing the number of splits and thus the period, at the cost of CPU time. As an example, for some 1M reads simulation from a Streptococcus pneumoniae genome, default Sparrowhawk with ntHash2 took around 26 seconds, while with the six splits ntHash it took 33 seconds.