A beginner's guide to fitting PopPUNK models

By John Lees

PopPUNK now has a lot of different models available, which can make it hard to know where to start, or to tell if you’ve done the right thing when fitting one to your data.

Some questions I’ll address:

tl;dr

- Don’t fit a model if you don’t have to.

- Try and use a refine/boundary model.

- Make sure your component near the origin is sensible (not too big or too small), don’t just rely on the network score.

- Check your clusters on a tree, in microreact or by somehow visualising them.

Do you need to fit a new model?

If there is an existing one you can download from databases then you can usually forgo this step entirely. As well as avoiding extra work and validation, you’ll also get consistent cluster names with other studies, which is a big advantage.

If your species isn’t listed, then you are going to need to fit a model. If you’re happy with your fit, we’d encourage you to share it with us (no need to share genome data) so we can add it to the database list. Others will be able to benefit from it, and it will build momentum for your nomenclature.

The other case is where the given model isn’t exactly the resolution you want (too many,

or not enough clusters). In this case you probably want to try something like

--multi-boundary to get a few alternatives to compare.

A bad time to fit a new model is if you have a different dataset but the same species as an existing model – it’s always worth trying the existing model first.

Should I subsample my data?

No, but you should definitely run the QC on it, and be fairly strict about including samples. It’s often possible to get an assignment afterwards for any you exclude at this step.

Which model should I use?

See https://poppunk.readthedocs.io/en/latest/model_fitting.html

The ideal model is usually one with a 2D boundary: it’s simple, fast to assign new samples with, and very portable.

How do we get there though? Usually in two steps: first by fitting a BGMM or DBSCAN model, then running a second refine model. But here’s a list of possible approaches:

Threshold

If you want to define a simple core distance cutoff, this is easily done with a threshold model, which is just a special case of 2D boundary models. You need to know/choose where to join the boundary, so you may need to try a few values and see if your clusters are any good. But these are totally valid and often useful models.

BGMM

This is really only a useful starting point if you have a small number of samples (at most a few hundred) and you have clear ellipse shaped features in the core-distance plot. It does a pretty good job of find density centroids however, so can be useful to find points to run with manual start.

Changing/iterating different values of the number of components --K is rarely useful, as there is almost always enough

data to support larger numbers of components.

We’ve found this the best way to make initial models with small amounts of data, but as there is little information on a specific boundary their performance can degrade as larger numbers of samples are added. So it’s usually better to refine it, or re-fit when a larger number of samples are obtained.

DBSCAN

This is a pretty useful way to get a starting point for subsequent model refinement.

The problem with DBSCAN models is that:

- The within-strain component, the most important one, is frequently too small and includes a scatter of points near the origin, giving far too many clusters.

- They are relatively slow to assign to (this may improve in future, with GPU acceleration).

- They are a few package dependencies, which have not remained backwards compatible.

As DBSCAN model can leave points unassigned (noise points; plotted in black), if you have a lot of these the network may be sparser than expected and lead to less consistent clustering (maybe? I don’t think we’ve ever actually seen this in practise). So it’s usually better to run refinement on them.

Refine

This is the canonical way to get a 2D boundary model. Model refinement has many options and flavours, but it all essentially works like this:

- Define a start and end point, and draw a line between them.

- Draw boundaries perpendicular to this line.

- For each of these boundaries, try using this as a model, and assess the cluster quality using a network score.

- Pick the boundary which gave the best network score.

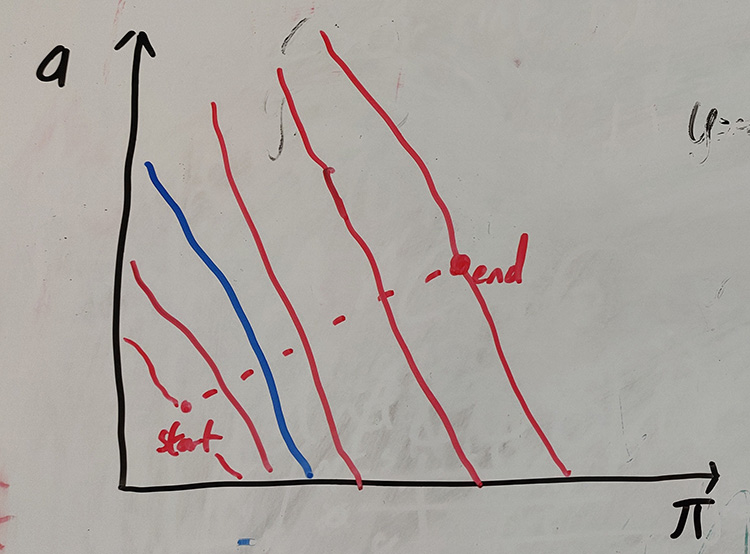

Cartoon of the refine process. A line is drawn from start to end, and boundaries constructed perpendicular to this (red lines). The blue line with the highest network score is chosen as the output.

The start and end point are defined as the clusters closests and second closest to the origin, in the first (BGMM or DBSCAN) model. The idea is that although all of these boundaries are likely to produce valid sets of clusters, the heuristics we use in the network score tend to produce ones which are useful for typical purposes.

Then the following modifications are possible:

- Define the start and end point manually, using

--manual-start. - Use a different network score which penalise cluster joining more (useful for very large datasets).

- Only test vertical or horizontal boundaries, i.e. core-only or accessory-only, with

--indiv-refine. - Output all of the tested boundary positions rather the top scoring one with

--multi-boundary. These can then be combined with iterative-PopPUNK. Great for multiple resolutions, or when trying to work out where you want the boundary to be. - Try different gradients of the boundary at each position (see below) with

--unconstrainedwhich is useful when the clusters are at a different angle to the line between start and end, at the cost of more computation.

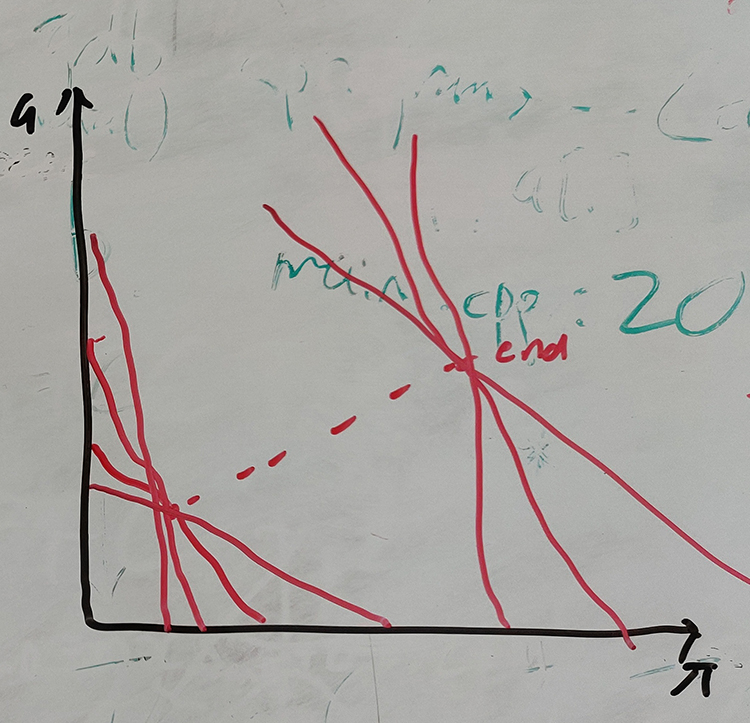

In unconstrained refinement, at each point different gradients of boundaries are also tested.

Lineage

Good for when you have closely related data, or trying to find subclusters. Only a single

parameter (--ranks) so very easy to try.

Are my clusters correct?

Clusters aren’t really right or wrong as there is no ground truth in real datasets. But clusters can be more or less useful, and this probably depends on your desired use of them.

Typically, PopPUNK clusters will broadly agree with a tree (i.e. there are not many polyphyletic clusters), but you might get more than you want, or not enough resolution. Resolution varying across the tree is not usually a problem.

Good checks include:

- How many clusters do I have? Too many, or not enough?

- Do I have any clearly merged clusters or high betweenness samples in the network?

- Are my clusters consistent with the tree (you can calculate the number of samples in the same clusters under each ancestor, for example).

- Does a visualisation/microreact look alright? Zoom in on some of the larger clusters.

My clusters don’t match MLST/CC

Perhaps first ask, does this matter? MLST is certainly not the ground truth! CC isn’t consistent between runs and datasets, so in my opinion shouldn’t be used (but is fine as a cluster alias, where its use has already been established).

One MLST may have many PopPUNK clusters, or one PopPUNK clusters may have many MLSTs (and you can even quantify this with some of the included scripts). Neither of these mean the clusters are ‘wrong’.

Generally these 7-gene schemes have poor resolution/not enough clusters, and sometimes even suffer from bigger problems (including a recombinant gene, so in some places you get too many types; or worse, a paralogous gene so assignment is not even clear). But if you think the MLST scheme is good, you can always pick the boundary that gives you the closest match between clusters.

In many commonly sequenced species, MLST schemes define a well-known nomenclature that you may wish

to keep referring too – the best way to keep this compatibility is with

--external-clustering.